- Introduction to Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Program

- Overall Information about Gender Role Conflict

- Gender Role Conflict Theory, Models, and Contexts

- Recently Published GRC Studies & Dissertations

- Published Journal Studies on GRC

- Dissertations Completed on GRC

- Symposia & Research Studies Presented at APA 1980-2015

- International Published Studies & Dissertations on GRC

- Diversity, Intersectionality, & Multicultural Published Studies

- Psychometrics of the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS)

- Factor Structure

- Confirmatory Factor Analyses

- Internal Consistency Reliability Data

- Internal Consistency & Reliability for 20 Diverse Samples

- Convergent & Divergent Validity of the GRCS Samples

- Normative Data on Diverse Men

- Classification of Dependent Variables & Constructs

- Authors, Samples & Measures with 200 GRC Guides

- Correlational, Moderators, and Mediator Variables Related to GRC

- GRC Research Hypotheses, Questions, and Contexts To be Explored

- Situational GRC Research Models

- 7 Research Questions/ Hypotheses on GRC & Empirical Evidence

- Important Cluster Categories of GRC Research References

- Research Models Assessing GRC and Hypotheses To Be Tested

- GRC Empirical Research Summary Publications

- Published Critiques of the GRCS & GRC Theory

- Clinically Focused Models, Journal Studies, Dissertations

- Psychoeducation Interventions with GRC

- Gender Role Journey Theory, Therapy, & Research

- Receiving Different Forms of the GRCS

- Receiving International Translations of the GRC

- Teaching the Psychology of Men Resource Webpage

- Video Lectures On The Gender Role Journey Curriculum & Additional Information

Future GRC Hypotheses, Models, and Context to be Explored

Generating hypotheses about GRC requires delineating the multiplicity of contexts that it occurs. This file guides future research by emphasizing a contextual approach in conceptualizing GRC research.

Thirty-two research questions related to GRC are stated on the predictive, moderating, and mediating effects of GRC.

Seven contexts to generate new GRC hypotheses are also discussed including: macros-societal, psycho-social-developmental, multicultural/diversity, situational, gender related indices, research, and therapeutic/psychoeducational interventions.

Future researchers and theoreticians can expand these contexts and hypotheses with their own ideas and creativity.

Seven Contextual Domains and 18 Research Questions on Men’s Gender Role Conflict*

The seven contextual domains of men’s GRC are based on the research reviewed in O’Neil (2008, 2015) and the previous research and theory in the psychology of men. The domains include: (a) Age, developmental stage, resolving developmental tasks, and gender role transitions; (b) Family interaction patterns, interpersonal situations, and peer relationships; (c) Masculinity ideology, norms, and conformity; (d) Psychological and physical health variables; (e) Men’s diversity - race, ethnicity, culture, class, religious, and sexual orientation as well as identity issues related to these categories; (f) Vulnerability variables related to violence, oppression, and abuse; and (g) Methods to help men resolve GRC through therapy and psychoeducational and preventive interventions. The seven domains provide an expanded theoretical basis for understanding the potential moderators and mediators of men’s GRC. To operationalize the seven contextual domains, 33 moderator and mediator research questions are enumerated in Table 1. These research questions can be pursued in the future research.

Table 1

Predictor, Moderator, and Mediator Hypotheses for Seven Contextual Domain for Expanded GRC Research Paradigm

Domain 1: Age, Developmental Stage, and Gender Role Transition

- Does age, developmental stage, or gender role transitions predict or moderate men and boy’s GRC?

- Does age, developmental stage, or gender role transitions mediate GRC in terms of problems outcomes for boys and men?

- Do developmental tasks or failure to complete them predict, moderate, or mediate problems for men?

- What developmental experiences influence men to conform to or violate masculinity ideology/norms that predict, moderate, or mediate GRC?

Domain 2: Family Interaction Patterns , Interpersonal, and Peer Relationships

- How do family interaction patterns, interpersonal situations, and peer relationships predict and moderate men’s GRC?

- How do family interaction patterns, interpersonal situations, and peer relationships mediate men’s GRC in terms of negative problem outcomes for men and others.

- Do families’ racial, ethnic, class, religious, and cultural backgrounds mediate men’s GRC in terms of negative problems outcomes for men and others? Is there intergenerational transfer of GRC?

- Does GRC predict or moderate intimacy, friendships, marital conflicts, parenting, and sexual functioning and dysfunctioning?

- Does intimacy, friendship, marital conflict, parenting and sexual functioning and dysfunctioning mediate men’s GRC in terms of negative problems outcomes for men and others?

Domain 3: Masculine Ideology, Norms, Conformity, Discrepancy

- Does masculinity ideology/norms predict and moderate GRC?

- Does masculinity ideology/norms mediate GRC in terms of negative problems outcomes for men and others?

- Does conformity to masculine ideology/norms or violation of them predict or moderate GRC?

- Does conformity to or violation of masculine ideology/norms mediate GRC in terms of negative problem outcomes for men and others?

- Does the discrepancy between real and ideal masculine ideology/norms within the man (discrepancy strain) predict or moderate GRC

- Does discrepancy strain mediate GRC in terms of negative problem outcomes for men and others?

Domain 4: Psychological and Health Variables

- Does GRC predict and moderate psychological and physical health problems for men and others?

- Does psychological and physical health problems mediate GRC in terms of negative outcomes for men and others?

Domain 5: Men’s Diversity: Racial, Cultural, Class, and Sexual Orientation

- Does racial, class, ethnic, religious, cultural, and sexual orientation variables predict and moderate GRC?

- Does racial, class, ethnic, religious, cultural, and sexual orientation variables mediate GRC in terms of problem outcomes for men and others?

- How do internally versus externally defined racial, class, ethnic, religious, cultural, and sexual identities predict, moderate, or mediate GRC in terms of problem outcomes for men and others? How do within group differences vary on these negative psychological outcomes?

- How does acculturation to status quo norms (white, middle class, heterosexual, capitalist) predict, moderate, or mediate problems outcomes for men. and others?

Domain 6: Vulnerability Variables Related to Violence, Oppression, and Abuse

- Does GRC predict or moderate men’s vulnerability to violence, abuse or discrimination of others?

- Is men’s vulnerability to violence, abuse and discrimination against others mediated by GRC in terms of problems outcome for men and others?

- Does GRC predict or moderate being a victim of oppression (racism, classism, ageism, sexism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism)?

- Is being a victim of oppression mediated by GRC in terms of problem outcomes for men and others?

- Does GRC predict or moderate the chances of a man becoming a victim of violence?

- Does being a victim of violence mediate GRC in terms of problems outcomes for men and others?

Domain 7: Methods To Help Men Resolve GRC: Therapy and Psychoeducational and Preventive Interventions

- Does GRC predict or moderate positive outcomes for men in therapy or other psychoeducational programs?

- Do different methods of help (techniques, theoretical approaches) mediate GRC in terms of positive outcomes for men in therapy?

- What client and therapists’ qualities, attitudes, and behaviors predict or moderate men’s GRC in terms of positive outcomes with men in therapy?

- What client or therapist qualities, attitudes, and behaviors mediate GRC in terms of positive outcomes with men in therapy?

- Do different ways of marketing men’s services predict or moderate whether men use the services?

- How do different ways to market men’s services mediate the way men use the services?

*Taken from:

O’Neil, J.M. (2008). Summarizing twenty-five years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. The Counseling Psychologist. 36, 358-445.

Predictive and Moderation Studies

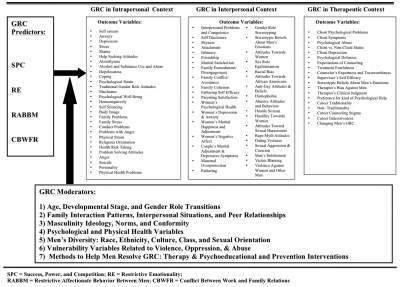

Figure 2 shows the predictive, moderating, and outcome variables related to men’s GRC. The purpose of Figure 2 is to help researchers generate prediction and moderator studies using the past research and theory. The top left arrow in Figure 2 shows the GRC predictors (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) relating to outcomes in the three GRC contexts shown in the top rectangles. These GRC contexts are the same research areas reviewed throughout this paper and include: (a) GRC in an intrapersonal context; (b) GRC in an interpersonal context; and (c) GRC in a therapeutic context.

Figure 2. Gender Role Conflict (GRC) Predictor Variables, Outcome Variables in Three Contexts, and Seven Moderators [click image for a larger version]

Prediction studies assess the variables to which GRC is significantly related. As shown in Figure 2, GRC patterns (SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR) have predicted 88 outcome variables shown in the three contextual rectangles. The overall prediction question is: what demographic, psychological, physiological, racial, cultural, social, familial, interpersonal, or situational variables significantly predict men’s GRC? Prediction studies are needed with contextual variables as part of the overall process of explaining what moderates and mediates GRC.

Moderators assess when or for whom a variable most strongly predicts or causes an outcome variable (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). Moderation variables affect the direction and/or the strength of a relation between independent variables (predictors) and a dependent or criterion variable (outcome) (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Moderation effects explain interaction effects or how one variable depends on the level of others. Figure 2 depicts how moderator studies can be conceptualized. The longer arrow on the left in Figure 2 shows the seven GRC moderators affecting the relationship between the four GRC predictors (SPC, RE, RABBM, & CBWFR) and the outcome variables in the three GRC contexts (intrapersonal, interpersonal and therapeutic). The seven moderators of men’s GRC are the contextual domains discussed in the previous sections: (a) age, developmental stage, resolving developmental tasks, and gender role transitions; (b) family interaction patterns, interpersonal situations, and peer relationships; (c) masculinity ideology, norms, and conformity; (d) psychological and physical health variables; (e) men’s diversity: race, ethnicity, culture, class, religious and sexual orientation and related identity issues; (f) vulnerability variables related to violence, oppression and abuse; and (g) methods to help men resolve GRC through therapy and preventive/psychoeducational interventions.

Moderator studies assess how variables contribute to fluctuations of high and low GRC. The overall moderator question is: How do demographic, psychological, physiological, racial, religious, cultural, social, familial, interpersonal, or situational variables significantly affect the direction and strength of GRC in predicting psychological outcomes for boys, men, and others. In other words, what contextual factors and situational contingencies differentiate those men who experience negative effects of GRC from those who do not? For moderation studies, theoretical rationales for hypothesized interactions are needed before creating hypotheses (Frazier et al., 2004). The previous elaborations on the seven contextual domains provide an initial theoretical rationale for assessing GRC moderator effects. Furthermore, 23 studies have found GRC to be moderated by different variables. These previous studies and the correlational data reported in this review provide initial empirical justification for testing the moderators of men’s GRC shown in Figure 2.

Mediator Studies

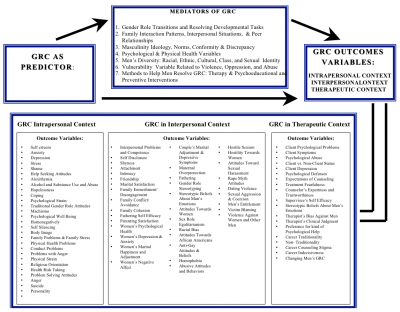

Mediator variables assess how and why one variable predicts or causes an outcome variable. Mediators assess the mechanism whereby a predictor influences an outcome and the underlying change process. Simply, mediators are the mechanisms through which an effect occurs. Figure 3 shows how mediator studies can be conceptualized.

Figure 3. GRC as Predictor, Seven Mediators of GRC, GRC Outcomes Variables in Three Contexts [click image for a larger version]

The overall research question is: How do mediation variables explain relationships between GRC and outcome variables? The figure shows the GRC predictors (SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR) in the upper left, rectangle directly related to the seven mediators (top center rectangle) and also related to the outcome variables in the far right and the large bottom rectangle. The mediators of GRC are the seven contextual domains defined earlier. The question captured by Figure 3 is: How and why does GRC cause men’s psychological problems and what variables mediate the relationship between GRC and those problems? In other words, do demographic, psychological, physiological, racial, religious, cultural, social, familial, social, interpersonal, and situational variables relate to GRC in producing negative outcomes for men and secondly what variables mediate GRC in terms of these outcomes?

There is both empirical and theoretical justification for the mediational research paradigm shown in Figure 3. For mediation analyses, predictors need to be significantly related to outcome variables (Frazier et al., 2004). As this research review has shown, SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR have been significantly correlated with the 88 outcome variables in the large rectangle in Figure 3 (See the longer arrow in the middle of Figure 3 for this relationship). Presumed predictors must also be theoretically related to the mediators (Frazier et al., 2004). Men’s GRC has been empirically or theoretically related to the proposed mediators as shown in Figure 3 (See shorter arrow in the upper left corner).

In summary, researchers can use Table 1 and Figures 2 and 3 to generate predictor, moderating, and mediating hypotheses for their own studies. What is a predictor, moderator, mediator, or outcome variable of GRC can be formulated by researchers using both the empirical and theoretical literature. The seven contextual domains in Figure 2 and 3 represent future programmatic areas of research for men’s GRC.

Contexts to Expand the Gender Role Conflict Construct and Theory

The dropdowns below show contexts to better understand men’s GRC. Contexts are important to explain how and why GRC occurs, how to mediate and recover from it. GRC contexts also help develop GRC theory and generate future research that is useful. The overall contexts are macro-societal, psychosocial and developmental, multicultural/situational, gender role related, research, and therapeutic/ psychoeducational.

Sections of this list of these assumptions and contexts taken from:

O’Neil, J.M. (2015). A call to action revisited: Personal reflections, contextual summary, and action plans. In J.M. O’Neil (Ed.) Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. (pp 339-351-28).Washington, D.C. : APA Publications.

Macro-Societal Contexts

Patriarchy; hegemonic masculinity; societal sexism; stereotypes and biases against men; societal discrimination; personal and institutional oppression (racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, etc.); social injustice; stereotyping about the socialization of boys and girls; differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies; and policy changes to promote change.

Assumptions:

- Macro-societal oppression is an organizer of society and include patriarchy, classism, racism, ageism, heterosexism, and other unjust discrimination that negatively affect men, women, and children.

- Macro-societal contexts negatively restricts male gender role socialization and include patriarchy, sexism, restrictive stereotypes, oppression and social injustices, and the differential socialization of boys and girls to sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies.

- Stereotypes and biases about men cause discrimination, GRC, oppression, and social injustices.

- The multicultural psychology of men studies the psychological costs of the macro-societal oppression that emanates from restrictive masculinity ideologies and GRC.

- Stereotypes and biases about men cause discrimination, GRC, oppression, and social injustices.

- A macro-societal analysis of men’s oppression explains how GRC and masculinity ideologies predict, moderate, mediate, and causes psychological problems, discrimination, and social injustices in men’s lives.

Psychosocial Developmental Contexts

Developmental tasks; psychosocial crises; demonstrating, resolving, re-evaluating, and integrating masculinity; phases of the gender role journey; gender role schemas; distorted gender role schemas; gender role transformation and growth; healthy and positive masculinity.

Assumptions:

- Gender role conflict and gender role transitions exist throughout the life cycle.

- Gender role development, transitions, and transformations are experienced while mastering the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises over the lifespan.

- Journeying with gender roles over the lifespan and managing gender role transitions are part of seeking positive and healthy masculinity.

- During the life stages, boys and men have varying degrees of restrictive masculinity ideology and GRC that affects psychosocial development of that developmental period.

- Numerous contextual, cultural, and situational factors affect how masculinity ideology and GRC impact psychosocial growth including mastering developmental tasks and psychosocial growth.

- Gender role transitions are necessary to master the developmental tasks and resolve the psychosocial crises.

- Mastering the developmental tasks and resolving the psychosocial crises require changes in a man’s gender role values and self-assumptions.

- Resolving gender role transitions related to developmental tasks and psychosocial crises involves demonstrating, resolving, redefining, and integrating gender role schemas related to masculinity and femininity ideologies.

- Restrictive masculinity ideology and the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, & CBWFR) may limit behavioral and emotional flexibility and interfere with the developmental tasks and the resolution of the psychosocial crises.

- Efforts to master the developmental tasks and resolve psychosocial crises can cause GRC.

- Distorted gender role schemas about masculinity and femininity may need correction to effectively resolve developmental tasks and the psychosocial crises.

- Fear of femininity and homophobia can interfere with effectively managing gender role transitions and resolving developmental tasks and psychosocial crises.

- Optimal development and positive masculinity are when the developmental tasks and psychosocial crises are resolved and gender role transitions have occurred, meaning that the changed self- assumptions about gender roles facilitate rather than delay further development.

- Journeying with one’s gender roles can facilitate gender role transitions and includes recognizing the costs of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- The transformation process of journeying with gender roles includes : a) changing psychological defenses, b) facing false assumptions, c) increasing internal dialogue about self, d) managing internal psychological warfare, and e) symbol manipulation.

Multicultural and Situational Contexts

Race; sex; class; socio-economic status; biology, age; unconsciousness; stage of life; ethnicity; cultural values; nationality; religious orientation; physical disability; sexual orientation; sexual identity; acculturation; oppression from discrimination; internalized oppression; family interaction patterns; being a victim; being unemployed, being homeless; being violent.

Assumptions:

- The multicultural psychology of men identifies the commonalities and differences between men (i.e. diversity)

- Situational, biological, unconscious, familial, multicultural, racial, and ethnic contingencies shape gender role identity in both positive and negative ways.

- At the micro-interpersonal level, contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies.

- The multicultural psychology of men studies the psychological costs of the macro-societal oppression that emanates from restrictive masculinity ideologies and GRC.

- Many different masculinity ideologies and identities exist based on racial, ethnic, age, nationality, religious, sexual orientation, and other situational indices of diversity that differentially predict, moderate, mediate, and cause GRC.

Gender Role Related Contexts

Gender role identity; fears of femininity; restrictive, sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies; patterns of gender role conflict; gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; defense mechanisms; male vulnerability; psychological and interpersonal problems; internalized oppression; violence from GRC.

Assumptions:

- Gender role identity is negatively affected by the macro-societal contexts that are oppressive.

- Many different masculinity ideologies and identities exist based on racial, ethnic, age, nationality, religious, sexual orientation, and other situational indices of diversity that differentially predict, moderate, mediate, and cause GRC.

- Three gender-related contexts that negatively affect men’s gender role identity are: restrictive and sexist masculinity and femininity ideologies, the fear of femininity, and distorted gender role schemas.

- Contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies, GRC, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- The effects of a restrictive gender role identity produce patterns of gender role conflict, defensiveness, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- Men experience vulnerability, societal discrimination, internalized oppression, psychological/emotional problems, and violence as a result of gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- GRC, defensiveness, and the gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations promote male vulnerability.

- The negative results of the macro-societal and the gender related contexts are internalized oppression, psychological and interpersonal problems, and violence.

- The micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives need to be studied to document both the positive and negative outcomes and consequences of male gender role socialization and GRC.

- Micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives can be understood with further conceptualization and work by applied behavioral scientists.

- Contextual, situational, and multicultural factors (i.e. race, sex, ethnicity, class, culture, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, acculturation, age, and other diversity indices) are related to men’s restrictive masculinity ideologies, GRC, and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

Research Contexts

GRC as predictor of men’s psychological problems; GRC as moderator of men psychological problems; GRC as mediators of men’s psychological problems; contextual and micro-contextual factors as predictors of GRC; GRC as a mediator of contextual and micro-contextual factors in predicting outcomes; descriptive-antecedent contexts; micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts; positive and negative situations related GRC; negative and positive behavior outcomes and consequences of gender related situations.

Assumptions:

- The micro-contextual, functional, and situational contexts of men’s lives need to be studied by applied behavioral scientists to document both the positive and negative outcomes and consequences of male gender role socialization and GRC.

- Therapists and psychoeducational programmers can use gender role transitions, gender role schemas, GRC and the gender role journey with men in therapy and during preventive interventions

- Therapeutic and psychoeducational interventions can be developed to help men and boys heal from their GRC and their gender related problems.

Therapeutic and Psychoeducational Contexts

Gender role journey; readiness and motivation to change; evaluations of restrictive gender roles, sexism, and other oppressions; stages of change (pre-contemplative, contemplative, preparation, action, and maintenance; client’s presenting problem; masculine specific conflicts; gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; deepening; gender role journey as portal; deconstruction of masculine and feminine roles; psychosocial assessment; gender role transitions; gender role schemas; distorted gender role schemas; macro-societal contexts; internalized oppression; GRC as the wound; GRC concealing the wound; GRC as a vehicle to discovering the wound; assessing masculinity ideology; assessing patterns of gender role conflict; assessing distorted gender role schemas; assessing gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; transitions in gender role journey phases; restrictive emotionality; success, power competition; restrictive affectionate behavior between men; conflict between work and family relations; homophobia; critical issues during therapy; psychoeducational program for boys and men; GRC’s relationship to student development theory; Chickering and Reissner’s identity vectors.

Assumptions:

- Gender role journey phases can be used as a therapeutic framework to help men in therapy and during psychoeducational programming.

- Assessing a man’s phase of the gender role journey gives insights into his readiness and motivation for change.

- Men can be invited to take the gender role journey by asking them if they are open to evaluate how restrictive gender roles, sexism, other oppressions have affected them.

- The three phases of the gender role journey parallel the stages of change in therapy (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance) and relate to the man’s problems that maintain problems and constrain change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010).

- Phase 1 and 2 of the gender role journey are considered to be unhealthy or at least unsettled phases of the gender role journey and reinforce masculine specific conflicts and other problems in men’ lives.

- The gender role journey can be a way of helping men discover their masculine specific conflicts and emotional wounds experienced as gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations.

- Facilitating a client’s gender role journey allows for deepening (Rabinowitz and Cochran, 2002) and prompt gender role transitions.

- The gender role journey serves as a possible portal to men’s problems. The gender role journey and GRC become a “….. a way to organize the thematic elements in the male client’s narrative as well as an entry or key to the deeper, emotional elements of images, words, thematic elements of the client’s inner psychological life (Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002, p.26).

- Deconstructing masculine and feminine gender roles and stereotypes is the primary way to experience the gender role journey and help men resolve their GRC.

- Facilitating the gender role journey can occur by using interviewing, consciousness raising, psychoeducation, bibliotherapy, and use of masculinity measures.

- Psychosocial assessment of the clients’ development, their gender role transitions, and distorted gender role schemas can facilitate the gender role journey.

- Providing clients macro-societal and diversity contexts to their gender role journey can help them discern how sexism and other oppressions have contributed to their psychological problems including internalized oppression.

- GRC is a multifaceted dynamic for both clients and the therapists and needs to be monitored during therapy for positive therapy outcomes.

- Normalizing human vulnerability, wounds, and pain is critical to facilitating the gender role journey.

- Psychological defenses may need to be assessed and worked with during the gender role journey.

- Clients’ GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can be a defenses that hide the portal and the masculine specific conflicts and inhibit movement through the gender role journey phases and the levels and processes of therapeutic change (Prochaska and Norcross, 2010; Brooks, 2010).

- Contextually, GRC may be a man’s wound, may conceal a man’s wounds, and may be a vehicle to discovering a man’s wounds.

- Assessing a man’s masculinity ideology, patterns of GRC, and distorted gender role schemas is critical during therapy.

- Assessing how the man devalues, restricts, and violate himself and others is key to finding the portal and resolving the GRC.

- Helping clients transition from one phase of the gender role journey to another by assessing and resolving the patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) can increase the deepening during the therapeutic process.

- The critical issue of transitioning men from one stage of change to another through the phases of the gender role journey occurs best with the resolution of the RE, SPC, homophobia, and control issues.

- Healing from gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations requires insights assertiveness, self-efficacy, risk taking, and personal and professional activism.