Three Diagnostic Schemas to Assess Gender Role Conflict In Counseling and Psychotherapy

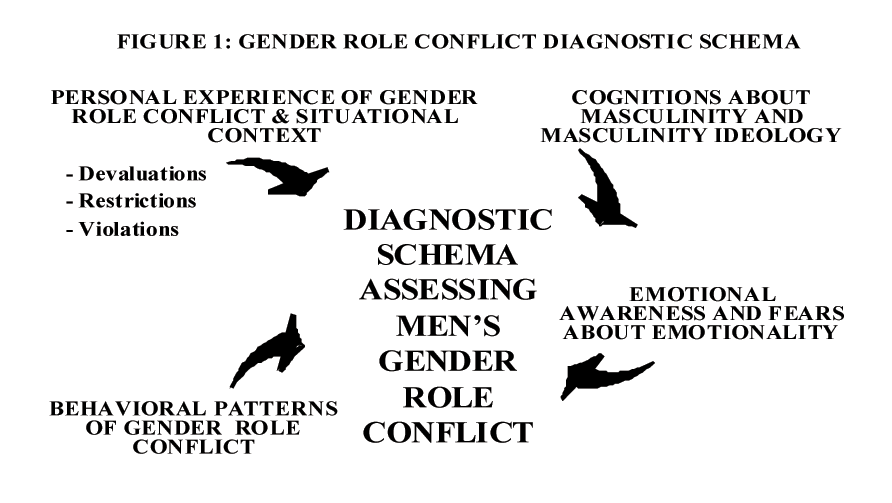

A diagnostic schema is shown in Figure 1 and includes four gender role conflict assessment domains: cognitions about masculinity and masculinity ideology, emotional awareness and fears about emotionality, behavioral patterns of gender role conflict, and personal experience of gender role conflict in situational contexts.

Cognitions about masculinity are how men think about gender roles in the context of relational, work, and family roles. The current theoretical concepts to describe men’s cognitions about masculinity are masculinity ideology (Pleck, 1995), masculine norms (Levant et al., 1992; Thompson, Grisanti, & Pleck, 1985), and masculine conformity (Mahalik et al., 2003). Emotional awareness is defined as the ability to label, experience, and express human emotions and the ability to receive others’ emotional expressions. Fears about emotionality result when emotions are not considered to be human experiences, but are seen as feminine and weak, and therefore antithetical to the expected masculine norms and ideology. The behavioral patterns of gender role conflict include restrictive emotionality, health care problems, obsession with achievement and success, restrictive and affectionate behavior between men, control, power, competition issues, and homophobia (O’Neil, 1981a, b; O’Neil et al., 1995). Empirical research over a 20 year period has shown these patterns are significantly related to higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress, aggression toward women, and other mental health problems (O’Neil, 2002). The personal experiences of gender role conflict are when men experience gender role devaluations, restrictions, or violations when they adhere to and deviate from the stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. The situational contexts of gender role conflict are gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations within the man, from others, or expressed toward others.

Expanded Diagnostic Schema to Assess Men’s GRC

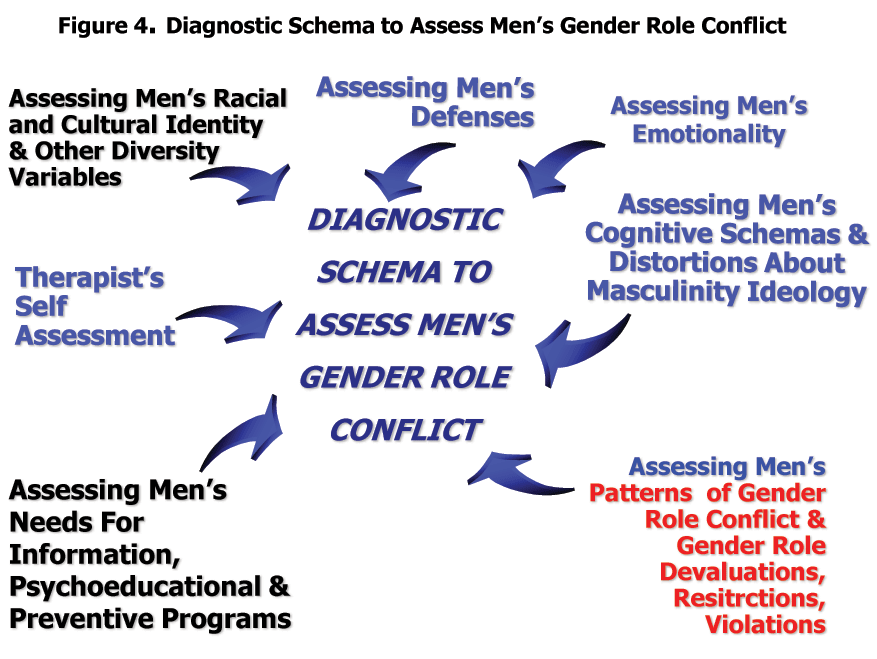

Clinically oriented researchers suggest that the culture of therapy is often incongruent with men’s masculinity ideology (Rochlen, 2005). This incongruence may require special assessments of men during therapy. Two diagnostic schemas to assess men’s GRC have been previously published (O’Neil, 1990; 2006) and are now expanded using the GRC research findings and the knowledge in the psychology of men. Figure 4 shows a diagnostic schema with seven GRC assessment domains including: (a) therapists’ self assessment; (b) diversity and oppression; (c) men’s defenses; (d) men’s emotionality and restrictive emotionality; (e) men’s distorted schemas about masculinity ideology; (f) men’s patterns of GRC and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations; and (g) men’s needs for information, psychoeducation, and preventive programs.

From O’Neil, 2008

The purpose of the diagnostic schema is to help therapists make assessments of men and better conceptualize clinical interventions in therapy and when preparing psychoeducational interventions. Each diagnostic domain is described below.

Therapists’ self assessment

In the first assessment domain therapists assess their ow knowledge and biases about men. Therapists can assess how much knowledge they have about the psychology of men and the psychological consequences of restrictive gender roles. No standard curriculum currently exists on what therapists should know when doing therapy with men. Until such a curriculum exists, therapists should consult with primary sources on doing therapy with men (Brooks & Good, 2001a; Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2000; Horne & Kiselica, 1999; Pollack & Levant, 1998; Lynch & Kilmartin, 1999; Mahalik, 1999b; Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002). Furthermore, this research review supports doing gender role assessments (Englar-Carlson, 2006; Brown, 1986) of men’s GRC using non-threatening structures that emphasize men’s strengths (Good, Gilbert, & Scher, 1990; Good & Mintz, 2001). Another critical area is assessing biases towards men. Therapists’ biases against men have been documented (Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1990) but not widely studied. Two studies have shown that therapists’ GRC significantly relates to having less liking for non traditional and homosexual men (Hayes, 1985; Wisch & Mahalik, 1999). Stereotyping and having biases against men are probably as frequent as they were with women in the 1970’s (Brodsky & Holroyd, 1975) and therefore need to be monitored and assessed during therapy. Assessing biases when doing therapy include three interrelated processes: therapists’ self assessment of their biases about men, assessing client biases, and monitoring transference and counter transference issues between therapist and client. This first assessment domain’s encourages therapists to have sufficient knowledge about the psychology of men and to assess how stereotypes and biases might affect the therapy process.

Assessing men’s diversity and oppression

This research review supports assessing men’s GRC contextually across diversity variables. Recognizing how GRC interacts with race, class, age, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and cultural values is critical. Studies have found that racial identity, ethnicity, and acculturation moderate and mediate GRC. How these diversity variables affect the therapeutic process is still relatively unknown. Recommendations have been made to extend APA’s multicultural competencies (American Psychological Association, 2003) to men’s GRC and the psychology of men (Liu, 2005; Wester, in press) These recommendations have given GRC “a multicultural face” by encouraging therapists to use knowledge about racial and cultural psychology (Carter, 2005 a, 2005b; Carney & Kahn, 1984; Sue, Arrendando, & McDavis, 1992) when doing therapy with men.

This multicultural thrust needs to be reinforced by emphasizing the social/political oppression of men. Men’s GRC needs to be understood in the context of sexism, racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, and any other oppression. Wester (in press) raises important questions for therapists working with men of different races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. Building on his central points, therapists should reflect on these additional questions when doing therapy with men: (a) Do my stereotypic beliefs about men affect my therapeutic judgment, with men who differ from me in terms race, class, age, sexual orientation, nationality or ethnicity? (b) Do men who deviate from traditional male stereotypes affect my judgment about their health or psychopathology? (c) Are my expectations, assessment processes, and therapeutic approaches different when treating men from different races, classes, sexual orientations, and ethnicities? (d) Is it important to assess male clients’ racial, cultural, or sexual identity in the context of their presenting problem? (e) Is it important to assess male clients’ experience of racism, sexism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, or any other form of oppression? Answers to these questions can enable the therapist to understand GRC in the context of men’s diversity and oppression.

Assessing men’s defenses

Assessing GRC may activate men’s psychological defenses particularly if the man is rigid, fragile, or in pain. Men can deny, project, and rationalize their depression, anxiety, and relationship problems. Only one study has correlated GRC to defense mechanisms (Mahalik et al., 1998) but masculine socialization has been conceptualized as a defensive process for decades (Blazina, 1997; Boehm, 1930; Geis, 1993; Jung, 1953; Levinson et al., 1978; O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999; Pollack, 1995). Assessing men’s defenses raises numerous therapeutic issues. First, therapists can assume that men’s defensiveness relates to protecting their gender role identity, dealing with threat, and avoiding devaluations and emasculation (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Defensiveness may serve various functions for male clients that therapists can actively assess. For example, defensiveness can mediate difficult and powerful emotions, help men cope with fears about appearing feminine or being emasculated, and help men defend against perceived losses of power and control. These defensive functions could be important vantage points to understand men in therapy. Furthermore, therapists can recognize that men’s defensiveness can produce restrictions in thought and behavior, emotional and cognitive distortions, over-reactions, cognitive blind spots, and increased potential for restriction and devaluations of others (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). One approach to working with men’s defense mechanisms is to define and discuss them in the therapy. Working with men’s defenses can open up new psychological space and facilitate greater self-processing and problem solving (Heppner et al., 2004). The therapist’s role is to help men understand their defensiveness and find more functional ways to process their thoughts and emotions during therapy.

Assessing men’s emotionality and restrictive emotionality

Men have problems with emotions when feelings are viewed as feminine, weak, and not part of being human. The assessment of men’s emotionality in therapy has substantial support from the research reviewed. RE significantly correlates with lower self-esteem, anxiety, depression, stress, shame, marital dissatisfaction, and negative attitudes toward women and gay men, and many other interpersonal restrictions.

Recommendations for assessing emotionality are related to recent critiques of men’s emotions (Heesacker, Prichard, 1992; Heesakaer, et al., 1999; Wester, Vogel, Pressly, & Heesacker, 2002; Wong, Pituch, & Rochlen, 2006; Wong & Rochlen, 2005). These papers challenge the stereotypes about male emotionality (Heesaker et al., 1999), suggest few differences may exist between male and female emotionality (Wester et al., 2002), and imply that men express feelings in nonverbal ways (Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Overall, therapists need to know that “…. men’s emotional behavior is not a stable property but a multidimensional construct with many causes, modes, and consequences “(Wong & Rochlen, 2005, p. 62). Researchers are beginning to integrate the science of emotions with the study of masculinity and explain the many possible causes of emotional behavior (Wong et al., 2006). Reconceptualizing, understanding, and honoring men’s diverse ways of expressing emotions is one of the most important issues for therapists.

The GRC research reviewed indicates that RE is significantly related to men’s problems with intimacy, self disclosure, attachment, male friendships, and problems in interpersonal relationships. These results can be useful to therapists when working with men who are uncomfortable with emotions during therapy. Therapists can explain that RE is primarily a socialized problem, emanating from sexist attitudes about men and emotions, and learned in families, schools, and in our larger society. Clients can explore how their RE was learned rather than conclude that it is just some personal deficit that cannot be changed. The costs of being emotionally restricted can be explained in terms of stress, depression, anxiety, and serious health problems. How men have lost their emotional potentials can be explored. Men can recognize that their “lost emotionality” may not have been their choice or fault, but recognize regenerating the expression of emotion in their lives is their responsibility.

Therapists can become experts in helping men develop emotional vocabularies and ways of expressing feelings. Men tend to hide emotions (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2003) and therefore, therapists can assume that some male clients may understate the personal pain in their lives. When men are emotionally restricted, one approach is to focus on their strengths of rational thought and behavioral action. Affirming a man’s strength can be important in developing trust and solidifying the therapeutic alliance. An affirmation of strength, however, may not be enough to help men with their deep pain and suffering. Many times emotional discharge and the release of pain are prerequisites for effective problem solving (Heppner, et al., 2004). Therefore, the assessment and nurturing of men’s emotional intelligence is a primary task for the therapist of men.

Assessing men’s distorted cognitive schemas about masculinity ideology

Men’s distorted cognitive schemas are related to men’s psychological problems and therefore are important for therapists to assess (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999; Mahalik, 1999a; 2001a). Cognitive schemas about masculinity are how men think about gender roles in the context of masculinity ideology, norms, and conformity (Levant et al., 1992; Mahalik et al., 2003; Pleck, 1995; Thompson, et al., 1985). Distorted cognitive schemas are exaggerated thoughts and feelings about masculinity ideology in a man’s life (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Distorted cognitive schemas occur when men experience pressure, fear, or anxiety about meeting or not meeting stereotypic notions of masculinity. Primary areas where schemas are distorted include power, control, success, sexuality, emotionality, affection, and self reliance. The research indicates that GRC is significantly related to problem areas like depression, anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, shame, and relationship problems that can make men vulnerable to cognitive distortions.

The relationship between cognitive distortions and GRC is theoretically and empirically undeveloped. However, assessing clients’ cognitive distortions related to SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR is recommended. Mahalik (1999a, 2001a) has specified four steps in helping men with their distorted cognitions including (a) assessing the specific areas of men’s cognitive distortion; (b) educating men to how cognitions, feelings, and behaviors are interrelated; (c) exploring the illogical nature and accuracy of the cognitive distortions; and (d) modifying the biased distortions with more rationality. These steps provide a useful framework for working with distorted cognitive schemas and GRC. Exploring and resolving men’s distortions about the meaning of therapy, strength, and help seeking can enhance the therapeutic alliance and set the stage for emotional release and effective problem solving.

Assessing men’s patterns of GRC and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations

The assessment of men’s patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) as part of the therapy process has strong support from the research. Direct questioning of the client’s understanding of their masculine identity and gender roles is one way to assess GRC. Additionally, the GRCS and the Gender Role Conflict Checklist (O’Neil, 1988) can be used as diagnostic tools in therapy (O’Neil, 2006; Robertson, 2006), in workshops (O’Neil, 1996, 2000; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988), and academic classes (O’Neil, 2001). The direct assessment of GRC can help clients develop a gender role vocabulary that can help them understand their psychological problems. Identifying GRC patterns can also stimulate emotional disclosure about the personal experience of being a man.

The research indicates that GRC is significantly related to men’s gender role self restrictions, self devaluation, and dysfunctional outcomes with others. The personal experience of gender role devaluations, restrictions, or violations can be assessed during therapy. How clients personally experience GRC can be understood by sensitive listening and through probing questions that helps men understand their gender role journeys (O’Neil, & Egan, 1992a; O’Neil, Egan, Owen, Murry, 1993; O’Neil, 1996; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). One of the primary roles for the therapist is to listen to the client’s story about being a man, interpret the story from a gender role perspective, and provide support for making healthy change.

Assessing men’s need for information, psychoeducation, and prevention programs

Many men need factual information about restrictive gender roles to understand how GRC affects their lives. Good and Mintz (2001) indicate that “such a focus on education and information may be especially useful for the male client…it plays into the stereotypic male strength of rationally examining information” (p. 594). Printed information on how GRC is related to men’s psychological problems can be given to clients. Clients can read about men’s issues outside of therapy using books that can help men reexamine their gender roles (Goldberg, 1977; Levant & Kopecky, 1995; Lynch & Kilmartin, 1999; Real, 1997). The therapist can prepare clients for these readings and consider the best time to share them to promote therapeutic gain. In one case study (O’Neil, 2006), the combination of having the client read about GRC and assess it in his life, resulted in a break through point in the therapy.

Many men can solve their problems outside of therapy if safe environments exist to explore their problems. These environments and psychoeducational interventions can be developed by mental health professionals. The creation of preventive and psychoeducational interventions for men with GRC is highly recommended. Only a handful of preventive programs have been empirically tested, but some do reveal that men can change their GRC and dysfunctional attitudes about gender roles (Davis & Liddell, 2002; Gertner, 1994; Kearney et al., 2004; McAnulty, 1996; Schwartz & Waldo, 2003; Schwartz et al., 2004). Preventive interventions for males of all ages are recommended, including elementary, middle, and high school students and even old men who have retired. Furthermore, GRC concepts could be integrated into divorce and parent education programs and specific programs for men who are violent or sexually aggressive. Changing strongly socialized attitudes about gender roles may require potent interventions over extended periods of time. The critical question is whether attitudinal change really translates to long term behavioral change. Furthermore, how to attract men to these psychoeducational programs may require creative advertising, since the research indicates that titles and formats can activate negative attitudes about help seeking (Blazina & Marks, 2001; Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1992; Rochlen et al., 2004, 2006). Assessing how men’s defenses and resistance may be activated before and during these programs can be critical in the overall effectiveness of these interventions.

Therapists’ self assessment

In the first assessment domain therapists assess their own knowledge and biases about men. Therapists can assess how much knowledge they have about the psychology of men and the psychological consequences of restrictive gender roles. No standard curriculum currently exists on what therapists should know when doing therapy with men. Until such a curriculum exists, therapists should consult with primary sources on doing therapy with men (Brooks & Good, 2001a; Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2000; Horne & Kiselica, 1999; Pollack & Levant, 1998; Lynch & Kilmartin, 1999; Mahalik, 1999b; Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002). Furthermore, this research review supports doing gender role assessments (Englar-Carlson, 2006; Brown, 1986) of men’s GRC using non-threatening structures that emphasize men’s strengths (Good, Gilbert, & Scher, 1990; Good & Mintz, 2001). Another critical area is assessing biases towards men. Therapists’ biases against men have been documented (Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1990) but not widely studied. Two studies have shown that therapists’ GRC significantly relates to having less liking for non traditional and homosexual men (Hayes, 1985; Wisch & Mahalik, 1999). Stereotyping and having biases against men are probably as frequent as they were with women in the 1970’s (Brodsky & Holroyd, 1975) and therefore need to be monitored and assessed during therapy. Assessing biases when doing therapy include three interrelated processes: therapists’ self assessment of their biases about men, assessing client biases, and monitoring transference and counter transference issues between therapist and client. This first assessment domain’s encourages therapists to have sufficient knowledge about the psychology of men and to assess how stereotypes and biases might affect the therapy process.

Assessing men’s diversity and oppression

This research review supports assessing men’s GRC contextually across diversity variables. Recognizing how GRC interacts with race, class, age, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and cultural values is critical. Studies have found that racial identity, ethnicity, and acculturation moderate and mediate GRC. How these diversity variables affect the therapeutic process is still relatively unknown. Recommendations have been made to extend APA’s multicultural competencies (American Psychological Association, 2003) to men’s GRC and the psychology of men (Liu, 2005; Wester, in press) These recommendations have given GRC “a multicultural face” by encouraging therapists to use knowledge about racial and cultural psychology (Carter, 2005 a, 2005b; Carney & Kahn, 1984; Sue, Arrendando, & McDavis, 1992) when doing therapy with men.

This multicultural thrust needs to be reinforced by emphasizing the social/political oppression of men. Men’s GRC needs to be understood in the context of sexism, racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, and any other oppression. Wester (in press) raises important questions for therapists working with men of different races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. Building on his central points, therapists should reflect on these additional questions when doing therapy with men: (a) Do my stereotypic beliefs about men affect my therapeutic judgment, with men who differ from me in terms race, class, age, sexual orientation, nationality or ethnicity? (b) Do men who deviate from traditional male stereotypes affect my judgment about their health or psychopathology? (c) Are my expectations, assessment processes, and therapeutic approaches different when treating men from different races, classes, sexual orientations, and ethnicities? (d) Is it important to assess male clients’ racial, cultural, or sexual identity in the context of their presenting problem? (e) Is it important to assess male clients’ experience of racism, sexism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, or any other form of oppression? Answers to these questions can enable the therapist to understand GRC in the context of men’s diversity and oppression.

Assessing men’s defenses

Assessing GRC may activate men’s psychological defenses particularly if the man is rigid, fragile, or in pain. Men can deny, project, and rationalize their depression, anxiety, and relationship problems. Only one study has correlated GRC to defense mechanisms (Mahalik et al., 1998) but masculine socialization has been conceptualized as a defensive process for decades (Blazina, 1997; Boehm, 1930; Geis, 1993; Jung, 1953; Levinson et al., 1978; O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999; Pollack, 1995). Assessing men’s defenses raises numerous therapeutic issues. First, therapists can assume that men’s defensiveness relates to protecting their gender role identity, dealing with threat, and avoiding devaluations and emasculation (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Defensiveness may serve various functions for male clients that therapists can actively assess. For example, defensiveness can mediate difficult and powerful emotions, help men cope with fears about appearing feminine or being emasculated, and help men defend against perceived losses of power and control. These defensive functions could be important vantage points to understand men in therapy. Furthermore, therapists can recognize that men’s defensiveness can produce restrictions in thought and behavior, emotional and cognitive distortions, over-reactions, cognitive blind spots, and increased potential for restriction and devaluations of others (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). One approach to working with men’s defense mechanisms is to define and discuss them in the therapy. Working with men’s defenses can open up new psychological space and facilitate greater self-processing and problem solving (Heppner et al., 2004). The therapist’s role is to help men understand their defensiveness and find more functional ways to process their thoughts and emotions during therapy.

Assessing men’s emotionality and restrictive emotionality

Men have problems with emotions when feelings are viewed as feminine, weak, and not part of being human. The assessment of men’s emotionality in therapy has substantial support from the research reviewed. RE significantly correlates with lower self-esteem, anxiety, depression, stress, shame, marital dissatisfaction, and negative attitudes toward women and gay men, and many other interpersonal restrictions.

Recommendations for assessing emotionality are related to recent critiques of men’s emotions (Heesacker, Prichard, 1992; Heesakaer, et al., 1999; Wester, Vogel, Pressly, & Heesacker, 2002; Wong, Pituch, & Rochlen, 2006; Wong & Rochlen, 2005). These papers challenge the stereotypes about male emotionality (Heesaker et al., 1999), suggest few differences may exist between male and female emotionality (Wester et al., 2002), and imply that men express feelings in nonverbal ways (Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Overall, therapists need to know that “…. men’s emotional behavior is not a stable property but a multidimensional construct with many causes, modes, and consequences “(Wong & Rochlen, 2005, p. 62). Researchers are beginning to integrate the science of emotions with the study of masculinity and explain the many possible causes of emotional behavior (Wong et al., 2006). Reconceptualizing, understanding, and honoring men’s diverse ways of expressing emotions is one of the most important issues for therapists.

The GRC research reviewed indicates that RE is significantly related to men’s problems with intimacy, self disclosure, attachment, male friendships, and problems in interpersonal relationships. These results can be useful to therapists when working with men who are uncomfortable with emotions during therapy. Therapists can explain that RE is primarily a socialized problem, emanating from sexist attitudes about men and emotions, and learned in families, schools, and in our larger society. Clients can explore how their RE was learned rather than conclude that it is just some personal deficit that cannot be changed. The costs of being emotionally restricted can be explained in terms of stress, depression, anxiety, and serious health problems. How men have lost their emotional potentials can be explored. Men can recognize that their “lost emotionality” may not have been their choice or fault, but recognize regenerating the expression of emotion in their lives is their responsibility.

Therapists can become experts in helping men develop emotional vocabularies and ways of expressing feelings. Men tend to hide emotions (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2003) and therefore, therapists can assume that some male clients may understate the personal pain in their lives. When men are emotionally restricted, one approach is to focus on their strengths of rational thought and behavioral action. Affirming a man’s strength can be important in developing trust and solidifying the therapeutic alliance. An affirmation of strength, however, may not be enough to help men with their deep pain and suffering. Many times emotional discharge and the release of pain are prerequisites for effective problem solving (Heppner, et al., 2004). Therefore, the assessment and nurturing of men’s emotional intelligence is a primary task for the therapist of men.

Assessing men’s distorted cognitive schemas about masculinity ideology

Men’s distorted cognitive schemas are related to men’s psychological problems and therefore are important for therapists to assess (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999; Mahalik, 1999a; 2001a). Cognitive schemas about masculinity are how men think about gender roles in the context of masculinity ideology, norms, and conformity (Levant et al., 1992; Mahalik et al., 2003; Pleck, 1995; Thompson, et al., 1985). Distorted cognitive schemas are exaggerated thoughts and feelings about masculinity ideology in a man’s life (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Distorted cognitive schemas occur when men experience pressure, fear, or anxiety about meeting or not meeting stereotypic notions of masculinity. Primary areas where schemas are distorted include power, control, success, sexuality, emotionality, affection, and self reliance. The research indicates that GRC is significantly related to problem areas like depression, anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, shame, and relationship problems that can make men vulnerable to cognitive distortions.

The relationship between cognitive distortions and GRC is theoretically and empirically undeveloped. However, assessing clients’ cognitive distortions related to SPC, RE, RABBM, and CBWFR is recommended. Mahalik (1999a, 2001a) has specified four steps in helping men with their distorted cognitions including (a) assessing the specific areas of men’s cognitive distortion; (b) educating men to how cognitions, feelings, and behaviors are interrelated; (c) exploring the illogical nature and accuracy of the cognitive distortions; and (d) modifying the biased distortions with more rationality. These steps provide a useful framework for working with distorted cognitive schemas and GRC. Exploring and resolving men’s distortions about the meaning of therapy, strength, and help seeking can enhance the therapeutic alliance and set the stage for emotional release and effective problem solving.

Assessing men’s patterns of GRC and gender role devaluations, restrictions, and violations

The assessment of men’s patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) as part of the therapy process has strong support from the research. Direct questioning of the client’s understanding of their masculine identity and gender roles is one way to assess GRC. Additionally, the GRCS and the Gender Role Conflict Checklist (O’Neil, 1988) can be used as diagnostic tools in therapy (O’Neil, 2006; Robertson, 2006), in workshops (O’Neil, 1996, 2000; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988), and academic classes (O’Neil, 2001). The direct assessment of GRC can help clients develop a gender role vocabulary that can help them understand their psychological problems. Identifying GRC patterns can also stimulate emotional disclosure about the personal experience of being a man.

The research indicates that GRC is significantly related to men’s gender role self restrictions, self devaluation, and dysfunctional outcomes with others. The personal experience of gender role devaluations, restrictions, or violations can be assessed during therapy. How clients personally experience GRC can be understood by sensitive listening and through probing questions that helps men understand their gender role journeys (O’Neil, & Egan, 1992a; O’Neil, Egan, Owen, Murry, 1993; O’Neil, 1996; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). One of the primary roles for the therapist is to listen to the client’s story about being a man, interpret the story from a gender role perspective, and provide support for making healthy change.

Assessing men’s need for information, psychoeducation, and prevention programs

Many men need factual information about restrictive gender roles to understand how GRC affects their lives. Good and Mintz (2001) indicate that “such a focus on education and information may be especially useful for the male client…it plays into the stereotypic male strength of rationally examining information” (p. 594). Printed information on how GRC is related to men’s psychological problems can be given to clients. Clients can read about men’s issues outside of therapy using books that can help men reexamine their gender roles (Goldberg, 1977; Levant & Kopecky, 1995; Lynch & Kilmartin, 1999; Real, 1997). The therapist can prepare clients for these readings and consider the best time to share them to promote therapeutic gain. In one case study (O’Neil, 2006), the combination of having the client read about GRC and assess it in his life, resulted in a break through point in the therapy.

Many men can solve their problems outside of therapy if safe environments exist to explore their problems. These environments and psychoeducational interventions can be developed by mental health professionals. The creation of preventive and psychoeducational interventions for men with GRC is highly recommended. Only a handful of preventive programs have been empirically tested, but some do reveal that men can change their GRC and dysfunctional attitudes about gender roles (Davis & Liddell, 2002; Gertner, 1994; Kearney et al., 2004; McAnulty, 1996; Schwartz & Waldo, 2003; Schwartz et al., 2004). Preventive interventions for males of all ages are recommended, including elementary, middle, and high school students and even old men who have retired. Furthermore, GRC concepts could be integrated into divorce and parent education programs and specific programs for men who are violent or sexually aggressive. Changing strongly socialized attitudes about gender roles may require potent interventions over extended periods of time. The critical question is whether attitudinal change really translates to long term behavioral change. Furthermore, how to attract men to these psychoeducational programs may require creative advertising, since the research indicates that titles and formats can activate negative attitudes about help seeking (Blazina & Marks, 2001; Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1992; Rochlen et al., 2004, 2006). Assessing how men’s defenses and resistance may be activated before and during these programs can be critical in the overall effectiveness of these interventions.

Diagnostic Schema to Assess Fathers During Therapy

Overt and Covert Fathering Contextual Model

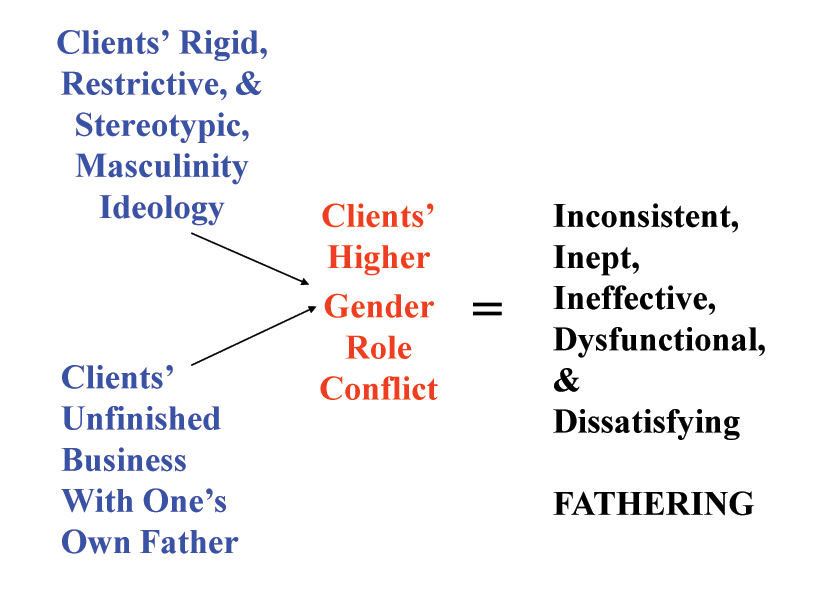

The covert contexts of fathering provide a rationale for clinicians to assess a father’s problems and psychological functioning. The model shown in Figure 1 depicts the overt and covert fathering contexts related to GRC and ineffective parenting. Arrows A1 and B1 imply that restrictive masculinity ideology, unfinished problems with one’s father, and the father wound are related to higher GRC. Furthermore, the model implies that higher GRC relates to inconsistent, inept, ineffective, dysfunctional, and dissatisfying fathering. Research and theory exist to support the relationship of masculinity ideology with GRC, as shown by arrow A1 (O’Neil, 2008; Pleck, 1995; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993). No empirical research has documented that clients’ unfinished business with their fathers or the father wound relate to GRC as is implied with arrow B1. There is some research indicating that higher GRC may relate to ineffective fathering for men in general (Alexander, 1999; DeFranc & Mahalik, 2002, McMahon, Winkel, & Luthar, 2002; O’Neil, 2008) as depicted in Figure 1, but no research has been completed with fathers who are clients. The concepts in Figure 1 are operationally defined and discussed in subsequent sections.

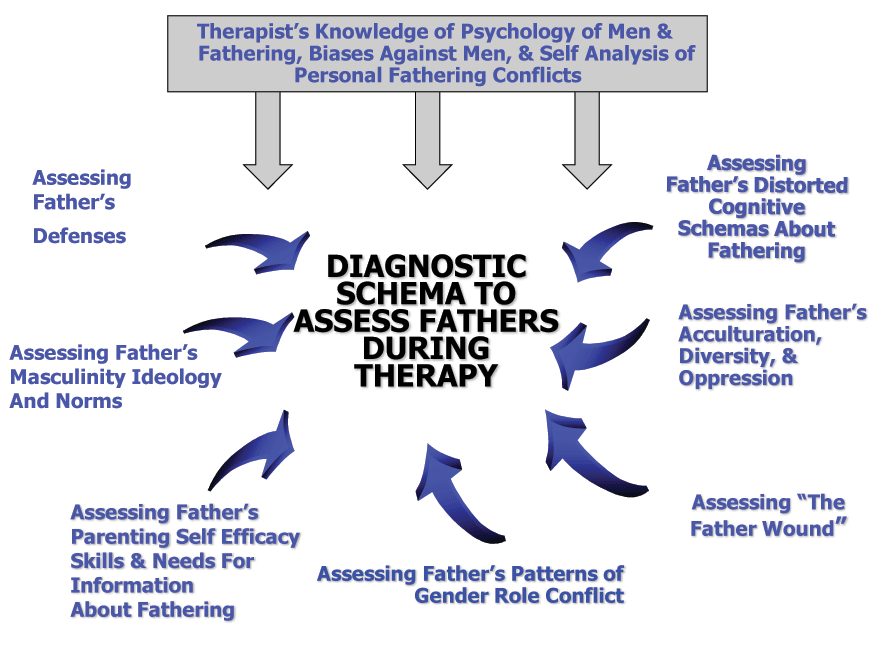

Diagnostic Schema to Assess Fathers During Therapy

Figure 3 depicts a diagnostic schema to assess fathers during therapy and includes eight domains that can be used to assess fathers in the covert or overt gender role contexts discussed earlier. The diagnostic schema’s goal is to provide domains that therapists can use when developing treatment plans with fathers. The eight domains are described below.

Therapist’s Knowledge of the Psychology of Men and Fathering, Bias Against Men, and Self Analysis of Personal Fathering Conflicts

This self assessment area has three dimensions. Therapists need to assess their knowledge about fathering and the psychology of men. Therapists can assess the knowledge they have on fathering and the psychological consequences of restrictive gender roles. No standard curriculum currently exists on what therapists should know when doing therapy with men in the context of GRC. Until such a curriculum exists, therapists should consult with the current authorities on therapy with men (Brooks & Good, 2001; Englar-Carlson & Stevens, 2006; Pollack & Levant, 1998; Rabinowitz & Cochran, 2002). Furthermore, therapists should also consult the literature on fathering and its relevance to helping men (Kiselica, 1995; Lamb, 2004; Osherson, 1987; Shapiro, 2001).

Another critical domain for therapists to assess is biases towards fathers and men. Therapists’ biases against men have been documented (Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1990), but few studies have assessed prejudice against fathers. Two studies have shown that therapists’ GRC significantly relates to having less liking for nontraditional and homosexual men (Hayes, 1985; Wisch & Mahalik, 1999). Current stereotyping and having biases against men are probably as frequent as they were with women in the 1970s (Brodsky & Holroyd, 1975). Therefore, therapists need to evaluate continuously the degree that their stereotypic biases may affect their assessment of fathers.

The third issue is therapists’ awareness of unfinished business or father wounds they might have with their own fathers. This is a critical counter transference issue when using fathering as a diagnostic category. Therapists can assess whether they have unresolved conflicts with their own fathers that may interfere with the therapy processes. Without this awareness, therapists may not recognize a client’s problems with fathering and avoid discussing it. Expressed more precisely, counter transference may impede the therapeutic process.

Assessing Father’s Masculinity Ideology and Norms

Assessing masculinity ideology and norms with fathers includes probing values and standards that define, restrict, and negatively affect a man’s life. There are numerous questions that can be asked about masculinity ideology during therapy. The critical question is what internalized masculine values does the client have that restrict his approaches to fathering? More specifically, how much do rigid, sexist, or stereotypic values impede positive fathering? Were these masculine values learned from the client’s own father? Therapeutic questions about a client’s masculinity ideology can be an important part of therapy with men. Many fathers may not know any alternative male values to replace restrictive and sexist ones. The therapist can help the client discern new values that are not sexist or restrictive. This therapeutic process involves discussing the healthy aspects of men’s gender roles and patterns of positive masculinity with fathers (O’Neil & Luján, in press; Luján & O’Neil, 2008). This means identifying men’s strengths, such as responsibility, courage, altruism, resiliency, service, protection of others, social justice, perseverance, generativity, and non violent problem solving. This kind of activity moves away from what is wrong with men and fathers to identifying the qualities that empower men to improve their fathering, their families, and their lives.

Assessing Father’s Defenses

Discussion of a man’s fathering and his past experiences as a son are issues that may activate psychological defenses. To our knowledge, no studies have correlated men’s defensiveness and problems with fathering. Defensiveness is important to assess because many theorists have conceptualized men’s socialization experiences as a defensive process (Boehm, 1930; Jung, 1953; O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). Defensiveness may serve various functions for fathers that therapists can actively assess. For example, defensiveness can mediate difficult and powerful emotions, help men cope with fears about appearing feminine or being emasculated, and help men protect against perceived losses of power and control. These defensive functions could be important vantage points to understand fathers in therapy. Additionally, therapists can point out that defensiveness can produce restrictions in thought and behavior, emotional and cognitive distortions, over-reactions, cognitive blind spots, and increased potential for restriction and devaluation of others (O’Neil & Nadeau, 1999). The client can consider how these defensive postures affect his parenting or other parts of his life.

Therapists can directly explore a client’s defensiveness about his father or fathering competence. One quick way to assess whether there is defensiveness related to a client’s fathering is to ask some pointed questions. For example, the client could be asked – How does your relationship with your father affect: a) your current problems as a man? b) your effectiveness as a father with your own children? Verbal and nonverbal responses to these questions could determine how to proceed with the therapeutic process. Wherever there are strong defenses, there are also usually deep emotions. The assessment of defensiveness about fathering can also be a strategy to uncover repressed or difficult emotions about one’s own father or fathering.

Assessing Father’s Distorted Cognitive Schemas About Fathering

Distorted cognitive schemas about fathering are inaccurate, narrow, and sexist views of gender roles as they impact fathering. Distorted cognitive schemas develop when men experience pressure, fear, or anxiety about meeting or deviating from stereotypic notions of masculinity. Many men have internalized a definition of fathering that is based on rigid and patriarchal values. The traditional definition of fathering exclusively focuses on provider roles, discipline, protection, and enforcement of a moral code. Traditional definitions of fathering have excluded important emotional, psychological, and educational processes. Therefore, traditional fathering may not include active involvement with such important male issues as emotional development, introspection, spiritual and sexual education, self confidence, fears of failure, problem solving, and decision making. Some fathers may define these issues as feminine, women’s work, and not part of traditional masculinity ideology.

What can therapists do with distorted cognitive schemas about fathering? Mahalik (1999, 2001) has identified four steps in helping men with their distorted cognitions including (a) assessing the specific areas of men’s cognitive distortion; (b) educating men about how cognitions, feelings, and behaviors are interrelated; (c) exploring the illogical nature and accuracy of the cognitive distortions; and (d) modifying the biased distortions with more rationality. These steps provide a useful framework for working with distorted cognitive schemas, GRC, and fathering issues. Exploring and resolving fathers’ distortions about the meaning of masculinity and fathering can enhance the therapeutic alliance and set the stage for emotional release and effective problem solving.

Assessing Father’s Acculturation, Diversity, and Oppression

There is diversity with fathering values and attitudes based on race, class, age, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and acculturation experience. Therapists and clients can explore how ethnic, racial, and acculturation variables affect fathering attitudes and values. Different races, classes, and ethnicities approach fathering in unique ways that need to be understood. For those fathers who have acculturated to American society, there may be contradictions in fathering values between this society and their society of origin. The therapist may need to help the man understand his parenting in the context of his racial, ethnic, and cultural identity (Wester, 2008). Therapists can help fathers reconcile conflicted values about fathering in terms of their cultural and bicultural identities. Therapists also need to consider how diversity variables can promote positive parenting and how they can produce barriers. Most importantly, these diversity issues need to be understood in the context of the overall societal demands on men that can be oppressive and sexist.

Personal oppression from sexism, racism, classism, ethnocentrism, heterosexism, or any other discrimination needs to be assessed in the context of any man’s fathering role. An oppressed man is usually angry, humiliated, emasculated, and vulnerable. For example, a father who cannot provide for his family (a basic masculine mandate in our society) because of racism is likely to feel angry, vulnerable, worthless, shamed, embarrassed, desperate, and inadequate as a man. When a man experiences these emotions, effective fathering may become irrelevant or less important. Survival and how to avoid further discrimination and humiliation may become the main priority. Some men will compensate for the oppression by becoming hypermasculine or aggressive. Oppression, discrimination, and poverty are not conducive to effective fathering and are serious barriers to many men’s desires to be positive fathers. Therapists need to have multicultural, acculturative, and diversity perspectives on fathering when working with a wide array of men.

Assessing the Father Wound

Assessment of the father wound during the therapy process is complex. Many times assessing the family of origin can help the therapist explore whether the client has internalized a father wound. Sometimes, simple exercises or homework assignments can uncover the wounds. For example, having a client draw a picture of his overall relationship with his father in the past or present can bring wounds into clear focus. Another activity could be writing a brief essay on the quality of the relationship with his father as a young boy. Having the client bring in a picture of his father can help focus the discussion of the father-son relationship. Many times, the path to healing is through increased compassion for the father’s wound as he experienced it.

Assessing Father’s Patterns of Gender Role Conflict

Therapists can assess the four empirically derived patterns of GRC (SPC, RE, RABBM, CBWFR) in the context of men’s fathering roles and functions (See Figure 2). The assessment of men’s patterns of GRC as part of the therapy process has support from the research. All four GRC patterns have significantly correlated with depression, anxiety, stress, low self esteem, shame, intimacy problems, marital dissatisfaction, homophobia, attachment problems, and abuses of women (O’Neil, 2008). The GRC patterns and these problems can impede effective fathering. For example, fathers need to be able to process their own emotions and the feelings of their children since family life can be emotionally charged. Constructive use of power and control is critical in successful parenting as sons and daughters test limits and challenge authority. Restriction of affectionate behavior can produce distance between fathers and their children. The CBWFR is a critical problem to be resolved because stress and fatigue do not contribute to effective fathering.

Direct questioning of clients about the degree to which they experience the patterns of gender role conflict is one way to assess fathers. Additionally, the Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS) and the Gender Role Conflict Checklist (O’Neil, 1988) can be used as diagnostic tools both in therapy (O’Neil, 2006; Robertson, 2006) and workshops for men (O’Neil, 1996, 2001; O’Neil & Roberts Carroll, 1988). The direct assessment of GRC can help clients develop a gender role vocabulary that can help them understand their psychological problems. Identifying GRC patterns can also stimulate discussion and emotional disclosure about the personal experience of fathering. One of the primary roles for the therapist is to listen to the client’s story about being a man, interpret the story from a gender role perspective, and provide support for making healthy changes.

Assessing Self Efficacy in Fathering and Need for Information About Fathering

In our literature search we found information about parenting self efficacy but no specific theory or measures on fathering self efficacy. Fathering self efficacy is defined as the father’s belief in his ability to effectively fulfill parental roles, functions, and responsibilities. As with attitudes about problem solving (Heppner, Witty Dixon, 2004), we hypothesize that a father’s belief in his ability to father effectively is one of the most critical variables in actually developing positive fathering. From our perspective, fathering self efficacy is more likely to occur if fathers have useful information on fathering roles, functions, and processes. Many fathers will have insufficient information about how to father, and this lack of information can produce insecurities about parenting or unrealistic norms about positive fathering. Therapists can be a source of information on the positive effects that fathers can have on their children. Books and articles can be given to fathers to help them develop a personal framework for parenting and how to create enjoyable fathering.

Many fathers can obtain needed information and fathering skills in psychoeducational group programs. These psychoeducational interventions can be developed by mental health professionals using the content in Figures 1-3. Changing strongly socialized attitudes about fatherhood may require potent interventions over extended periods of time. Furthermore, how to attract men to these fathering programs may require creative advertising. Research indicates that titles and formats can activate negative attitudes about help seeking (Blazina & Marks, 2001; Robertson & Fitzgerald, 1992; Rochlen, McKelley, & Pituch, 2006). Fathering programs should be described in positive terms that communicate men’s strengths and vitality.